I-Corps Experience Helped Chart 3D Health Solutions’ Path to Startup Success

Posted May 19, 2021

Karin Allenspach is a professor of translational health and small animal internal medicine at Iowa State University. Her colleague, Jonathan Mochel, is an associate professor of quantitative pharmacology. As co-founders of the Ames-based startup 3D Health Solutions, they began their entrepreneurial journey at Iowa State by going through the National Science Foundation (NSF) Innovation Corps (I-Corps) training during the 2018 spring cohort.

Allenspach and Mochel entered I-Corps with an idea they believed could greatly enhance the efficiency and predictability of the development of new treatments against various cancers and other life-threatening illnesses in both dogs and humans. After successfully completing the program, they walked away even more resolute that their idea had merit. Over the past three years, their resolve has been further galvanized through:

- A Research Collaboration Agreement (RCA) between Mochel, as principal investigator, and Iowa State and the Office of New Animal Drug Evaluation of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA);

- A Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) award of $225,000 from the National Science Foundation (NSF) that 3D Health Solutions received in 2019;

- A Regents Innovation Award in 2019;

- The company winning the top prize of $40,000 in the John Pappajohn Iowa Entrepreneurial Venture competition in 2020;

- Allenspach and Mochel receiving the 2020 Margaret B. Barry Cancer Research Program award, which is administered by the Iowa State Office of the Vice President for Research and given to faculty or professional and scientific (P&S) researchers to further cancer research, specifically in the College of Veterinary Medicine; and

- Winning the 2021 Iowa Biotech Showcase, a pitch competition for emerging biotech companies across various industries including ag tech, human health, medical devices, animal health and industrial/environmental biomaterials.

Perhaps most significant, 3D Health Solutions has entered into a development partnership with Boehringer Ingelheim, one of the largest pharmaceutical companies in the world.

A Novel Solution to Help Streamline Drug Development

Arguably the greatest challenge to improving animal and human health is the enormous time and financial commitments associated with developing new pharmaceutical disease solutions.

“Globally, the attrition rate in Phase 2 clinical drug trials is 95%. The R&D costs of each new drug molecule average in the area of $2.7 billion and the average development time is around 15 years,” Mochel said. “One of the most striking examples of treatment failure is Alzheimer’s Disease. In the U.S. alone, more than 5 million people are affected, resulting in more than $200 billion in health care costs. More than 400 clinical trials have been conducted over the past 14 years, and we still have no effective treatment for those afflicted by Alzheimer’s.”

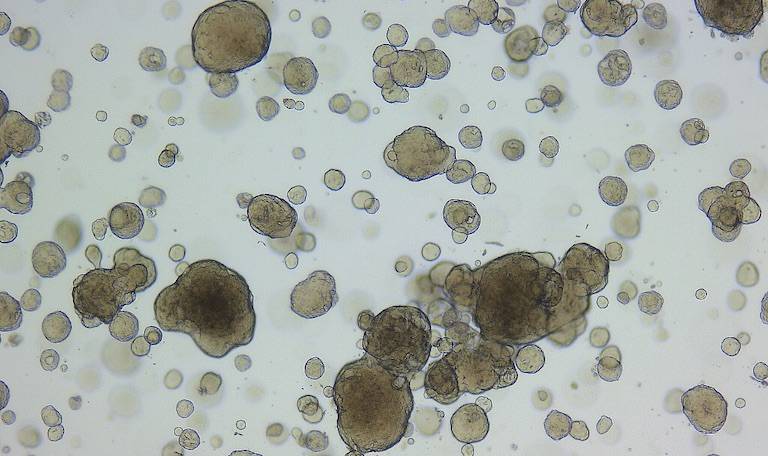

The innovation that Allenspach and Mochel have developed centers on creating mini-organs, or organoids, using stem cells from dogs to improve the accuracy and efficiency of the drug development life cycle.

“Our company is focused on developing canine mini-guts in a dish that are able to mimic key biological functions that provide accurate predictions of drug absorption following the administration of therapeutic drugs. This innovation will enable drug companies to better anticipate which drugs are most likely to deliver therapeutic benefits to patients while still being safe,” Mochel explained. “This is a breakthrough technology and we’re the only company in the U.S. to have access to it.”

The genetic background of dogs is quite similar to that of humans. Conventional drug-testing procedures frequently rely on dogs because of these similarities. In addition to concerns about animal testing, the results from a process that uses healthy dogs is of dubious value because drugs are not used to treat healthy patients. But 3D Health Solutions creates mini-organs from the stem cells of dogs that have spontaneously developed diseases similar to humans, including Alzheimer’s, cancer, or Crohn’s disease.

“We have an innovation that can fix the problem that only a very few drugs actually ever make it to market,” Allenspach said. “We can help decrease health care costs by using dog mini organs in a dish as a faster and cheaper solution to drug testing that will help us bring new medicines that we urgently need to solve the big problems in animal and human health.”

The First Step Down the Entrepreneurial Path

The I-Corps experience of 2018 played an important role in helping Allenspach and Mochel shape 3D Health Solutions into the company it is today. One of the cornerstone elements of I-Corps training is customer discovery – innovators reaching out to actual potential customers to gauge their level of interest in the product they’re trying to develop. The reality is, any new technology is only as good as its ability to meet the needs of the market.

“I have to admit, I went into I-Corps completely naïve,” Allenspach said. “The customers interviews were challenging . . . and humbling. A lot of the feedback we got was like, ‘This is a really good idea but forget about it. It’ll never work. People have been trying this for 50 years. Why would you be able to solve it.’ This was good to hear, but it didn’t deter us.”

One of the real benefits that came from the initial customer interviews is how it helped Allenspach, Mochel and their team sharpen their pitch for subsequent customer engagements.

“The I-Corps team made us prepare an ‘elevator pitch’ to communicate why we’re working on this innovation and the need in the market we’re addressing,” Allenspach said. “The elevator pitch was supposed to be an invitation to encourage potential customers to ask questions and tell us why the situation we’re working on is a problem for them, and share the frustrations this problem is causing them.”

“What I found interesting,” she added, “is that after we refined our elevator pitch, I was never able to get all the way through it, even though it was only a minute or two. Every time I started, the customer would say ‘Let me stop you right there. I know what you’re talking about and here’s why it’s so frustrating.’ That validated that we understood our customers’ problem and they understood what we were trying to do.”

Ultimately, the customer discovery process that Allenspach and Mochel started in I-Corps, and continued when they went through the ISU Startup Factory program, generated 80 separate interviews that proved invaluable in refining and validating the value of their mini organoid concept.

“Kris Johansen (ISU I-Corps site co-leader) shared her experience of how her startup failed because they didn’t receive customer feedback quickly enough. That really struck me, because it’s the sort of thing you don’t get when you’re doing research in the so-called ‘ivory tower,’” Allenspach said. “It really reinforced that your technology needs to suit whoever your customer is in the real world, otherwise it won’t go anywhere.”

The Iowa State I-Corps site includes three cohorts each year – spring, summer and fall. Allenspach and Mochel both recommend the program for campus innovators, and offer these words of advice:

“You have to really, really believe in your idea,” Allenspach said. “Don’t let others try to persuade you that you can’t do it because you’re an academic, or a woman, or something else. Go for it. The experience is eye-opening. It’s also very fulfilling to see something that is your idea potentially make it to market. So, again, you have to believe in your idea, but you also have to believe in yourself.”

Mochel said, “If you come in thinking you have the best idea, but you’re unwilling to listen to anybody or absorb constructive feedback, you’re going to fail. In the end, I-Corps is an exercise in humility, but also perseverance. As a researcher and an academic, there are so many times that you want to just give up, but you need to have someone support and validate you. That’s what you get from the I-Corps experience and the connections you make through the program.”